Instruments

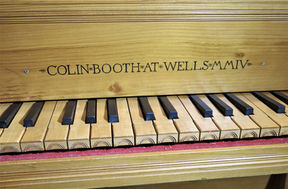

Single-Strung Italian Harpsichord - Now Sold

I can presently offer a fine example of my popular single-strung Italian harpsichord. Since these fine instruments are no longer made, this is an unusual opportunity.

Dated 2004, it is refurbished and in perfect playing order, with a mature, rich tone.

Compass GG/BB -c3.

Transposing either a=415/440, or 440/466. Black Delrin plectra. Some very minor marks to the exterior are not easy to spot, and the condition is generally excellent.

There is no padded cover, but the price includes music desk, tuning lever, hinged and removable wooden lid, and spare strings and plectra.

Now Sold.

My Previous Work:

My final years as an instrument maker included some successful departures:

I no longer take commissions. However, one or two instruments, either new or refurbished, may be available from time to time for immediate sale (see above post).

As a harpsichord maker I have had the pleasure of supplying around three hundred customers, including a high percentage of professional musicians. Some leading harpsichordists have acquired at least four instruments, including Colin Tilney (Canada) and Steven Devine (UK).

I keep a selection of instruments for my own pleasure, for concert use and recording, and continue to hire out harpsichords for concerts. A few instruments are also available for long-term rental, within a restricted geographical area. Please contact me for information on these services.

Here are some examples of my work.

Ottavini

Eight of these little instruments were made. All are now sold, but I kept one for my own use.

I have now built eight ottavini, based on an anonymous original in Vienna. These charming, tiny Italian instruments have a sweet but pungent tone.

The photos show the stages of construction, through to the first completed pair.

(Ottavini are small spinets or virginals at four foot pitch. Harpsichords at octave pitch were more common in the early Renaissance, but lessened in popularity later on, whereas the ottavino remained very popular as a domestic instrument in Italy until the 19th century.)

New Harpsichord after Celini 1661

This new harpsichord was built in the first part of 2016. It is based on the design of the Celini original harpsichord, and will be my personal recital instrument. Although still very new, the sound is remarkable.

Frequently asked questions

There are certain questions a harpsichord-maker is often asked. This page gives me the opportunity to answer these questions much more fully than time usually allows.

How long does it take to make a harpsichord ?

Early in my working life as a maker I was asked to build a rectangular Italian virginal, to a silly deadline. I had little equipment, a small workshop, and mostly hand-tools. I made the whole instrument in three weeks, somehow… less time than I would take today, forty years later, with a workshop full of machinery to help. I have always preferred to take my time, however, and needn’t comment on the improvement in finish! I don’t overrun on delivery-dates, but usually make several instruments at once, at least in their early stages.

Today my workshop produces between two and eight instruments per year, depending on their size and complication. Like other English makers, I experienced a boom in the 1980s; employed two full-time assistants, and produced at least a dozen per year. Now I work on my own, but sub-contract to a skilled wood-turner. I’m much happier with the consistent quality of my work today, and feel that the instruments really are the product of a single pair of hands. Also, not having to do a regular 9 to 5 day unless I choose, means that harpsichord-practising gets less neglected!

Italian instruments have always been at the heart of my output - and of my interest, but in recent times the demand has been equally strong for German models, often for large 2-manuals. Although the construction of both types is closely related, this leads to a rather different style of working. Long ago I got into the habit of preparing parts for several instruments at once, and then finishing them individually. This makes sense for small Italian instruments, and still saves time for a lot of operations; but today I find that larger German harpsichords take so long from start to finish (often more than a year), that the workshop seems permanently crammed with uncompleted work. At times there have been nine instruments there, mostly part-made. At home I house my main personal instruments for playing… between two and four, and usually another being played-in for a customer. This is important: a harpsichord needs proper playing-in after completion, like a car used to require running-in. Then it gets regulated again before delivery. Even then it will not sound the way it will a year or two later. As with all instruments made of wood, there is a slow and little-understood development of tone which only time and playing can achieve. So there is a variable but considerable amount of time to be added at the end of the process, in addition to that needed to make the instrument itself.

What woods do you use in harpsichord-making ?

Different harpsichords are made from different timbers, and there are always several incorporated in any instrument. In Italy harpsichords were traditionally usually made from Cypress, which was a durable and plentiful local timber there. It had the virtues of being resonant enough for use as a soundboard, but tough enough to use, cut thinly, for light-weight cases too. I use triple-dried Cedar of Lebanon: this is grown in England, where it was widely planted in parkland, often more than two hundred years ago. When force-dried, it has very similar characteristics to Cypress, even down to the aromatic smell. I like the idea of using timber grown in the area where the instrument is made, when this doesn’t conflict with the instrument’s musical personality. Some Italian harpsichords had cases of Poplar, and I use local Poplar too. Smaller quantities of other English timbers are used for certain parts: Oak for the wrestplank, and Beech for bridges, for example. I use imported Pine for bottoms and lids.

German harpsichords were eclectic in design and materials: all these timbers were used, with the exception of Cedar or Cypress. Hardwoods like Walnut were used for part of the cases, and Pine for other parts, like the spine. Some parts were sometimes laminated! The 1728 Zell harpsichord in Hamburg has a laminated cheekpiece, but the curved bentside was, surprisingly, still kept solid. Similar combinations of woods can be found in 17th century French instruments, which have become a focus of mine in recent years.

Thirty years ago Michael Thomas pointed out that just using the same wood as the original is not enough. It may even be counter-productive if you are aiming to imitate the sound of an original closely. Over the years a maker gets to know, almost intuitively, the kind of sound a piece of wood will give when incorporated. This is not just when he traditionally listens to the ring of a piece of soundboard-wood when he taps it. Case-wood can also have a great effect on the tone of an instrument. Very old wood is often much lighter in weight than new wood, even when this has been force-dried. There is a lot of mystery about wood still, thank heaven!

How did you become a harpsichord-maker ?

Which came first - making or playing ?

I usually answer, that on leaving university I did not know what to do with my Classics degree (that’s Latin and Greek, by the way.) This is unfair to my former lecturers, since I had made up my mind to try to be a harpsichord-maker long before the end of the course. I had always played early music, but an added stimulus was being frequently ejected from the room in the university music department where their harpsichord lay, because I was not a music student. I made my first spinet over one summer vacation, and that was it.

The two activities, playing the music and making the instruments, continued hand-in-hand, and still do so. There is no doubt that each has a valuable contribution to the success of the other, although as the decades pass, the rigours involved in woodwork have to be carefully considered, particularly if an important playing engagement is on the horizon. Stiffness of the fingers and arms can play havoc with the production of trills!

What is your personal approach to harpsichord-making ?

Many harpsichord-makers began by making accurate copies of original instruments, and then in later years felt freer to inject their personal creativity into the design. This is a very sensible approach but, looking back, I find I have done the reverse. I always based my instruments on originals (and was told quite early on that I was someone who could produce something of the elusive quality of an original), but I find myself working today more closely with the original designs than ever before.

Today compromise is less important, since we have finally thrown off the idea of an all-purpose harpsichord. Even customers who will need to use their instrument flexibly, to play music from the English virginalists through to Bach, recognise that it is going to be better for one of these than for the other. They will take particular pleasure in the response the instrument can provide, when the most suitable music is being played on it.

There are a lot of instruments claiming to be copies, which an experienced eye could discover to be something rather different. Makers know the points at which they have not strictly copied an original, and should be willing to reveal these to a client, if that client has “a copy” in mind. Fortunately, it is generally recognised now that a copy can really mean no more than a conscious imitation of an original. Moreover, today’s players have had decades to learn how different kinds of harpsichord - and different makers - behave. It has been shown that two makers conscientiously building accurate copies of the same original, will produce instruments which sound remarkably different. In any case, building a musical instrument is rather like performing a piece of music: the creator will inevitably reveal him or herself in the finished article.